on

"A Clockwork Orange" is Kubrick's realisation of an Orwellian fantasy

Alex DeLarge in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’, 1971

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange tries to be many things in a nifty way. A satire on state control, a study of the effervescent youth, and an outlandish extol of the Ninth Symphony. Set in Britain, Orange is an English film using a made-up vocabulary derived from Russian that is delightful to listen to. With sentences such as: “Come and get one in the yarbles if you have any yarbles you eunuch jelly, thou”, and words like “malenky”, “rassoodocks”, “devotchka”, one would want to simply keep listening to it.

PLOT

Alexander DeLarge is a troubled, delinquent charming youth with an extended appetite for knifing, violence, sex, and rapes. Along with three accomplices - Pete, Dim, and Georgie, they embark on daring nightly criminal enterprises and find themselves wealthy both monetarily and carnally. With beating up bums on the street, breaking into homes to rape wifes in front of their husbands, robbery, and every progressive crime so heinous and inciting in nature, we start to disgust Alex, at the very least. But life is good for Alex, a meek set of parents, Basil, his pet snake for company, and music, oh yes, especially Ludwig van’s Ninth Symphony that he so adores. It is only after a failed theft and accidental murder of the victim that Alex finds himself sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment, a term that he despises. He is tortured and manhandled in the cells and the brutality of prison life soon makes us symphathise with our poor Alex. A poor, young lad, albeit slightly lost. Isn’t he? So, when the opportune time comes to sign up for a new psychological treatment — Ludivico treatment — by the Government in accord with its new agenda of not punishing criminals, but to “cure” them altogether, Alex jumps at the opportunity — not so much as for a sincere remorse for his past but as a means of escape from the “hellhole and human zoo”. It might not be forward of us to think of Alex as Kubrick’s own toy, a vehicle he yields to sway our sentiments at will.

Scene from ACO

THE LUDIVICO TREATMENT

This is an interesting juncture of the film wherein the oppressive and impulsive Alex is turned into a submissive, meek, subordinate via a brutal fourteen-day regime of brainwashing, and chemically conditioned repulsion for violence and (accidentally) music, especially Ninth Symphony that so poignantly accompanied the videos on Holocaust and Nazis as they were shown to Alex with eyelid-locked apparatus. What emerged out of this is a totally different man, one who won’t advance for the usual “good in-out” on an inviting naked woman but go so far as to lick the boot of an oppressor if asked to do so. And it is this moment that we begin to question the rationality and effectiveness of the method adopted by the Government. Yes, Alex is permanently conditioned to denounce crime and violence but where has the state left him the power of decision. He might not be the first to start a fight but what is alarming is the realisation that he won’t be able to defend himself if he finds himself in one. Thus, the much-lauded brainwashing technique is reduced to a masquerading method to turn the masses into submissive, little cattle. You might have guessed where Kubrick is going with this. Such procedure, if conducted en masse with the determination and resources easily accessible to the state, would surely pave the way for a totalitarian, state-controlled regime with no dissent against the dictator. An Orwellian fantasy realised.

Scene from ACO

PLOT CONTINUED

But oh, I digress much from our good, ol’ Alex, one who is forever robbed of experiencing the joys of the Ninth. The reformation does come at a cost. And it is shown most vividly by his rendezvous with his old accomplices, Dim and Georgie, who have now assumed the post of police-officers, young and brash, just how the Government would like the law-enforcers to be. The meeting isn’t pleasant. Old balance books are settled. And Alex, left to his own accord, finds himself at the cozy residence of none other than the revolting writer whose wife he had wronged. Alex reasons that due to his proboscis mask at the time of crime, the man won’t be unable to identify him straight away. But he does. And we know it. Particulaly impressed by Kubrick who manages to hold the suspense so properly in this scene. A suicide attempt by Alex goes awry after he is locked in a room and tortured by the Ninth, a remote-control, a vulnerability deliberately introduced by the state. With broken bones, he lays on his hospital bed, only to be visited by Minister of the Interior, the champion of the Ludivico technique. An understanding is reached between the two as “friends” and we are left to ponder the meaning of it all as a wild rape fantasy pops into Alex’s head making us ask the question, “What changed?”

THEMES AND MOTIFS

Orange is ambitious in the range of themes it tries to portray and comment on. Now, let’s proceed to dismantle the many motifs and references, something to always look forward to in a Kubrick. The first thing that I noticed was the usage of a peculiar vocabulary, a peculiarity that is closer to amusement just by the acoustic qualities of the sounds. The most provoking motif, although not a special one, is Kubrick’s fetish with bare female skin (Eyes Wide Shut unmistakenly comes to mind) and the need to explicitly display it, as a celebration of the female form or just a perverted downslide, that we may may never know. Classical music adorns the background score of a greater part of the movie and the dramatic and impressive usage of music to complement grosteque scenes of violence and assault is again very Kubrick-esque. Circling back to, perhaps, the most visually noticeable feature that is the mise-en-scene. There is general consensus as to the importance that Kubrick associates with his set design, props, and lighting. We are reminded of the rebellious writer’s quirky and modernist house, an unforgettable piece of interior designing. Same goes for Mr. DeLarge’s residence and the arousing Korova Milk Bar. The brilliant usage of bright and saturated colors along with patterns and motifs goes a long way in consolidating the images in the viewer’s head a long time after the movie is over, something Kubrick knew and exploited to his advantage well.

And sample this dialogue of Alex with an old roadside bum who he later thrashes:

Bum: It's no world for an old man any longer.

What kind of a world is it at all?

Men on the moon.

Men spinning around the earth.

And there's not no attention paid...

...to earthly law and order no more.

Nothing the usage of the Cockney English, delight for the ears to listen but not much practical. This is the style adopted throughout the script. This particular dialogue stands apart because there isn’t anything along this spirit in the movie, the regurgitory rant of the old against the new world order, that is.

Scene from ACO

CONCLUSION

Ah, so much analysis but are we left with anything more than what we came here with? Perhaps not. The highly effective Ludivico technique is (thankfully) fictional but does it imply the absence of a eqaully potent technique out there currently employed by so-called law-enforcers? Is it morally correct or even beneficial to punish the offenders? Or will it make more sense to “cure” them? ACO asks a lot of questions or maybe none at all. But who cares if it is good cinema, innit?

PS: Kinda ironic I’m composing this while listening to van Beethoven’s Ninth hehe.

PPS: Alex’s pet snake is named Basil. Can you believe that?! I’m immortalized in a Kubrick film. Still feels unreal man. LOL.

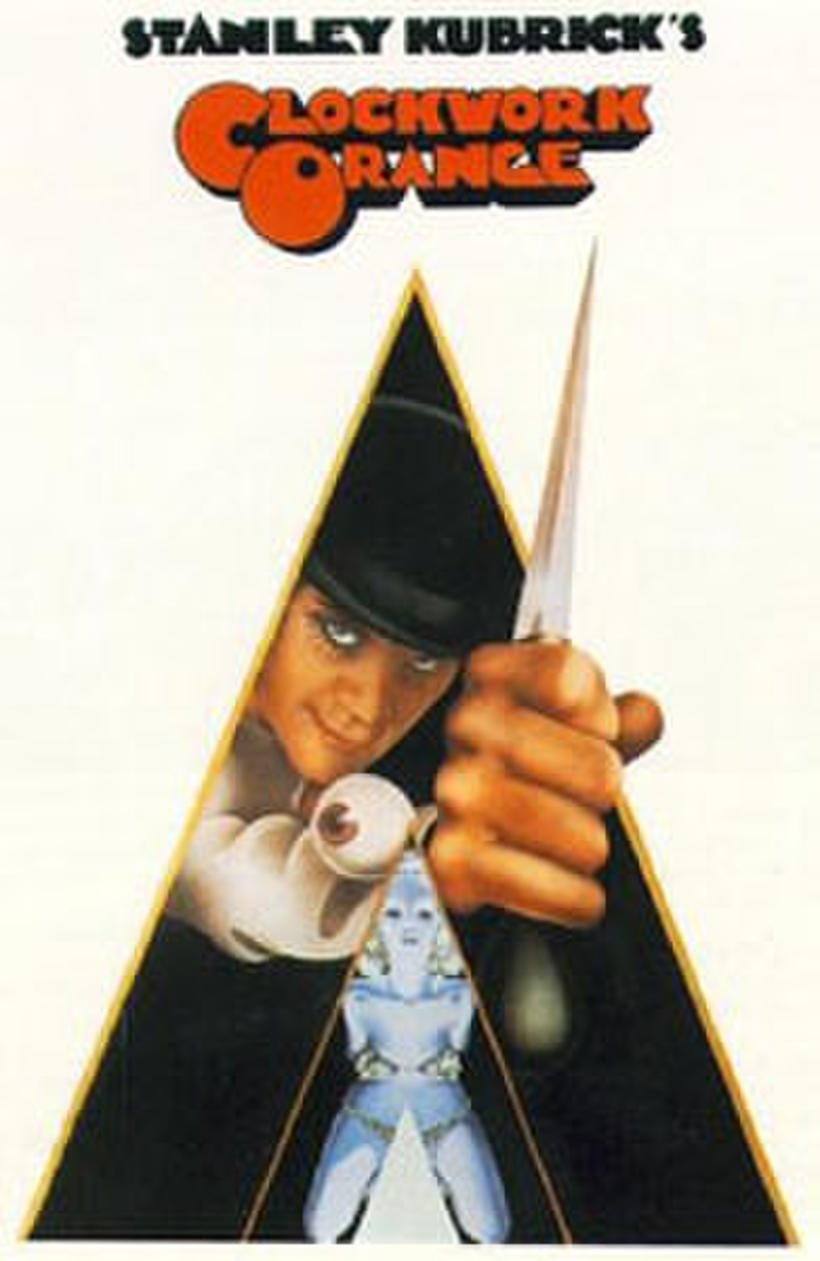

Film poster for ‘A Clockwork Orange’